Introduction

Counterfeit mill test reports (MTRs) and forged heat numbers are serious risks for combined cycle power plants and substations. In an industry where piping and pressure equipment operate at high pressure and temperature, even a small deviation in material quality can lead to catastrophic failure. Unfortunately, unscrupulous suppliers sometimes provide documentation that looks legitimate but does not correspond to the actual materials delivered. This post explains how these counterfeit documents arise, what an authentic MTR should contain, how to recognise red flags, and what steps procurement and quality professionals can take to verify documentation.

Why Counterfeit Certificates Exist

Counterfeiting of mill test reports thrives where there is a lack of oversight and a strong incentive to cut costs. Small workshops or traders may mix heat numbers, mislabel material grades or fabricate documentation to move stock quickly. Some may not fully understand the importance of traceability and think that any certificate will satisfy the buyer. Others knowingly falsify documents to hide the fact that they are supplying a lower grade material than specified. In global supply chains, language barriers, different standards and varied levels of regulatory enforcement further contribute to the problem. When equipment is shipped halfway across the world, verifying authenticity becomes more challenging.

What a Genuine MTR Contains

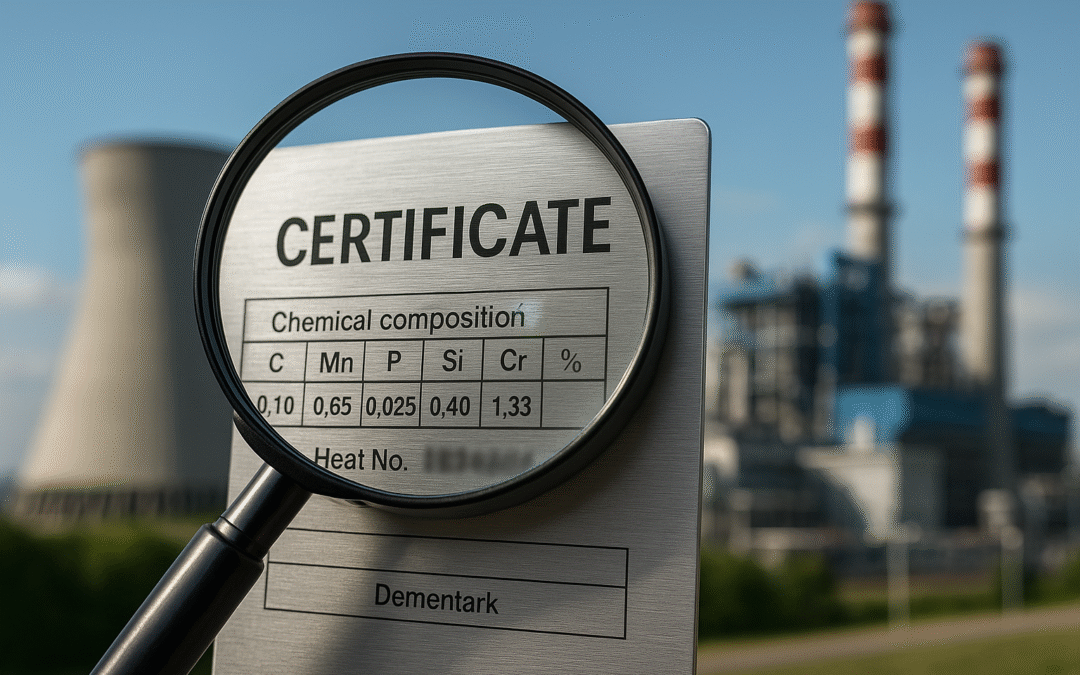

A genuine mill test report is more than a piece of paper. It is a formal document that records the chemical composition and mechanical properties of a batch of steel or alloy. The report should clearly state:

- The specification and grade (such as ASME SA-335 P91 or EN 10216-2).

- The heat number, which identifies the specific melt or batch of material from which the product was made.

- The chemical composition, with the measured percentages of elements like carbon, chromium, nickel, molybdenum and vanadium.

- Mechanical properties such as tensile strength, yield strength and impact values tested at specified temperatures.

- The type of inspection certificate, for example EN 10204 3.1 or 3.2, and the relevant norms used for testing.

- Signatures or stamps from the manufacturer’s quality assurance department or an independent inspector.

This data should align with the requirements of the purchase order and applicable codes. Values should fall within permissible ranges, and any supplementary requirements specified by the client should be referenced.

Red Flags for Fake Documents

There are several common signs that a mill test report or heat number may be fake or manipulated. Identical chemical and mechanical values repeated across different orders or heats are a major warning sign; in reality, there will always be slight variation. Heat numbers on the paperwork that do not match the marking on the actual component indicate a break in traceability. Look out for inconsistent fonts or file names that suggest the document has been copied and edited. If the certificate claims to be an EN 10204 3.1 or 3.2 document but lacks any reference to the testing standard or has no inspector’s signature, it is likely not valid. Another red flag is when there is no test temperature noted for impact results or when high-temperature creep properties are missing even though these were required.

Verifying Heat Numbers

Heat numbers are a key part of the traceability chain. These numbers are usually stamped or engraved directly on the material or product. When you receive a shipment, check that the heat number on the physical item matches the number on the MTR. If there are multiple pieces with different heat numbers, each one should have its own certificate. Beware of situations where a fabricator has cut and welded materials from different heats but only provides a single MTR; each heat needs its own documentation. In cases where stamping may have been removed during machining, the supplier should provide a method of transferring the heat number, such as a traveller or log sheet. If in doubt, request confirmation from the original mill or arrange for a third-party witness test.

Steps to Verify Certificates

Procurement and quality teams can take practical steps to minimise the risk of receiving counterfeit documentation. First, always request EN 10204 3.1 or 3.2 certificates for pressure parts and safety-critical items. Second, cross-check the chemical composition and mechanical properties against the relevant specification; if the values fall outside the permitted range, reject the material. Third, verify that the heat number on the item matches the number on the certificate and that the certificate lists the correct product form and dimensions. Fourth, look for the testing standards cited on the report (such as ASTM A370 for mechanical tests). If the supplier has not indicated the standard or has referenced outdated standards, ask for clarification. Finally, when large quantities of material are involved, consider random sampling and testing by an independent laboratory to confirm the chemical composition. This may seem burdensome, but it is far less costly than dealing with a failure later.

Case Study: The Cost of Not Verifying

A combined cycle plant in South Asia once purchased a batch of high-pressure boiler tubes that came with what appeared to be EN 10204 3.1 certificates. The plant’s quality control department relied on the paperwork and did not perform any further checks. Within months of commissioning, several tubes ruptured, causing an unplanned shutdown. Investigation revealed that the tubes were actually made from a lower grade material and had inadequate creep strength. The MTRs had been copied from genuine certificates but the heat numbers had been altered. Had the plant required third-party verification or performed random chemical analysis, the issue would have been caught before installation.

Conclusion

In a market flooded with suppliers of varying reliability, you must treat mill test reports and heat numbers with the same scrutiny you would give to a safety inspection. Counterfeit documentation is not always easy to spot, but simple checks—matching heat numbers, verifying chemistry and mechanical data, insisting on proper certificate types and looking out for inconsistencies—can protect your project. As an independent compliance consultant, I specialise in helping owners and engineers implement these checks. If you want peace of mind that your materials are what they claim to be, reach out for a review of your next purchase order or a training session for your team. Authentic materials are not just a requirement; they are the difference between smooth operations and costly failures.