Ensuring Safety Relief Valves Meet Chemical and Mechanical Requirements

Safety relief valves are the last line of defence in a high-pressure power plant. When a boiler or pressure vessel experiences an overpressure condition, these valves open to vent steam or fluid and prevent catastrophic failure. In combined cycle power plants and high-energy substations, relief valves protect steam drums, reheater outlets, condenser off-gas, lube-oil systems, and the main feedwater network. Because a relief valve will only open in an emergency, you don’t get a second chance. If the valve’s body or disc is made from inferior or wrong material, it may seize, crack, or corrode, turning a protective device into a point of failure. That’s why compliance goes beyond nameplates: you must verify the chemical composition and mechanical properties of every valve body, bonnet, spring, and seat.

Understanding safety relief valves and their materials

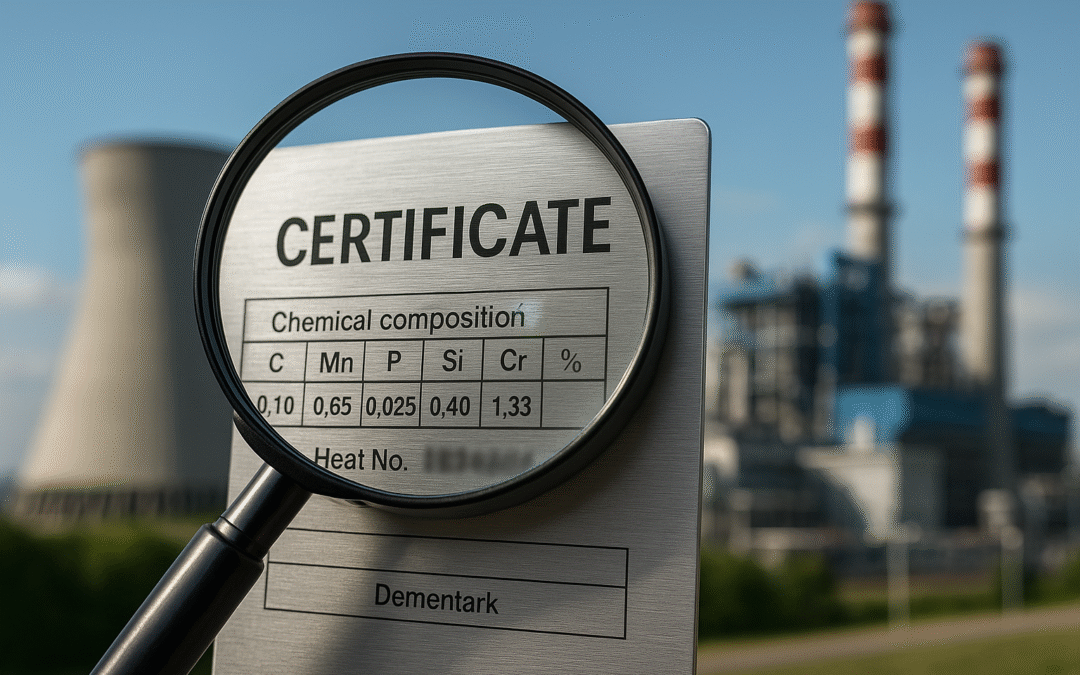

Relief valves are pressure-retaining components subject to strict codes. In the U.S., ASME Section I, VIII, and B31.1 set standards, along with API 520/521 and local jurisdiction rules. Materials vary by service: carbon steels like ASTM A216 WCB or WCC are used for moderate temperatures; low alloy steels like A217 WC6 and WC9 for high temperature steam; stainless steels like A351 CF8M or CF3M for corrosive or high-chloride environments; and high-chromium materials like F91 or F92 for ultra-supercritical conditions. Each grade has a defined chemical composition (percentages of C, Mn, Cr, Mo, Ni, etc.) and mechanical properties (yield strength, tensile strength, elongation, impact values) that ensure it can handle its design pressure and temperature. If you substitute a cheaper grade or accept a valve with unknown chemistry, you risk creep rupture, stress corrosion cracking, or early

Chemical composition: the foundation of integrity

A genuine valve body or disc should have its heat number and material grade stamped on it. This heat number links the part to its Material Test Report (MTR), which lists exact chemical composition. For example, ASTM A217 WC6 must contain 0.05–0.20% carbon, 0.80–1.10% chromium, and 0.50–0.80% molybdenum. These alloying elements provide creep resistance at high temperatures. If carbon is too high, the material may become brittle; if chromium or molybdenum are low, the alloy may lack high-temperature strength. The MTR also shows the steel-making process and reference standards. When receiving valves, procurement engineers should request EN 10204 3.1 certificates with specific heat and cast numbers, and verify that the chemical analysis matches the grade and project specification.

Mechanical properties: verifying strength and ductility

Chemical composition alone doesn’t guarantee performance. Mechanical test data—yield strength, tensile strength, elongation, and impact toughness—show how the material behaves under load. ASME Section II Part D provides allowable stresses for each grade; for example, ASTM A217 WC9 has a minimum tensile strength of 585 MPa and yield strength of 415 MPa at room temperature. Impact testing ensures the material isn’t brittle at low temperatures. A relief valve used on a condensate line may see colder fluids during start-up; if the impact energy is too low, the disc or body may crack when the valve snaps open. These properties must be measured on test coupons from the same heat; they should be recorded in the MTR and cross-checked aga

Standards and certification pathways

In Europe, EN 10213 and EN 10283 cover steel castings for pressure equipment, while EN 12516 details valve design and testing. These complement EN 10204 for inspection documents. In the U.S., the National Board requires relief valves to be certified and stamped with the “NB” mark, and to be assembled by authorized assemblers. Under all regimes, the manufacturer must provide an inspection document (3.1 or 3.2) that includes chemical and mechanical test results. Type 3.2 certification, involving a third-party inspector or customer representative, is often used for high-risk or regulated equipment.

Steps to ensure compliance when purchasing relief valves

- Define the design conditions: Determine pressure, temperature, fluid, and service (steam, condensate, gas) to select the correct material grade and valve type (safety, relief, pilot-operated, etc.).

- Specify material and certificate requirements in the RFQ: State the required material grade (e.g., A217 WC6) and the mandatory certificate type (EN 10204 3.1 or 3.2). For hydrogen or sour services, specify additional testing (HIC, SSC).

- Review manufacturer MTRs and certificates: Upon receiving bids, request and examine MTRs. Check that the heat number on the MTR matches the stamping on valve bodies and bonnets. Compare chemical composition against ASTM/EN grade ranges and mechanical properties against code minima.

- Verify dimensions and wall thickness: Ensure body castings meet ASME B16.34 requirements for pressure-temperature ratings. Wall thickness influences stress and creep life.

- Inspect spring and trim materials: The springs, discs, and seats must also be appropriate materials (e.g., Inconel X-750 springs for high temperature service). Request MTRs for these components as well.

- Conduct third-party or purchaser witness testing: For critical applications, witness hydrostatic and seat leakage tests. Confirm set pressure and blowdown meet API 527 limits.

- Document heat number traceability: Keep a register linking each valve’s heat number to its MTR and installation location. This is vital for future audits or replacements.

- Audit suppliers: Visit foundries or machining shops to ensure they maintain proper heat identification throughout machining, assembly, and testing.

Common pitfalls and red flags

Despite clear procedures, problems still arise. Some suppliers deliver valves with EN 10204 2.2 test reports masquerading as 3.1, or MTRs that list generic chemistry values not specific to the delivered heat. Others use incorrect seat or spring materials that cannot handle temperature extremes. In worst cases, unscrupulous vendors replace original bodies with cheaper castings after factory inspection, or mis-stamp heat numbers to hide mixing of heats. Watch for MTRs with identical values across multiple orders, or mechanical test results copied from literature rather than from actual tests. A sudden increase in valve weight or finish may signal substitution. When in doubt, request chemical and PMI testing at receipt.

Case study

A combined cycle plant in the Midwest purchased a batch of safety relief valves for its high-pressure feedwater system. The specification required ASTM A217 WC6 bodies and EN 10204 3.1 certification. Due to schedule pressure, procurement accepted the vendor’s promise that certificates would follow. Once installed, several valves started weeping during commissioning. Investigation revealed that the bodies were made from a low-alloy steel with insufficient chromium and molybdenum. The vendor had used leftover castings from another project and re-stamped them. The MTRs were generic 2.2 declarations with no heat number. The weeping was due to accelerated corrosion and inadequate mechanical strength. The client had to replace all valves at their own cost and delay plant startup. This could have been prevented by insisting on 3.1 certificates and verifying heat numbers before installation.

Conclusion: turning compliance into reliability

Safety relief valves are not commodity items. They are engineered pressure-retaining devices whose performance depends on the chemical and mechanical integrity of every component. In a combined cycle plant, a single valve failure can shut down a turbine or, worse, cause a safety incident. By demanding EN 10204 3.1/3.2 certificates, cross-checking chemical and mechanical data against codes, and ensuring heat-number traceability, owners and EPCs protect themselves from hidden liabilities. As an independent compliance consultant, I help clients interpret MTRs, audit valve suppliers, and set up systems for verifying certificates and heat numbers. If you’re procuring critical valves or replacing them in an existing plant, reach out. Together, we’ll ensure that the protective devices you rely on are as reliable as the plant you’re building.inst code requirements.fatigue failure.